|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

Lisa Shapter |

|

Lisa Shapter is an alumna of the Breadloaf Young Writers’ Conference and a member of Codex Writers’ Group. She has worked as an editor’s assistant for a major press, at several libraries, and has completed her apprenticeship to an ABAA antiquarian book dealer. She lives in New England and is completing a series of novels set in this story’s universe. She is also a member of Broad Universe, the Carl Brandon Society, the Dramatists’ Guild, and the New England Science Fiction Association. She is author of:

-"No Woman, No Plaything" in Kaleidotrope, Autumn

2012 Populating far-flung colonies in outer space is a piece of cake, right? Not for Lisa Shapter's heroine and her young son. Prepare to have your brain... and your sense of proprietary stretched in Planet 38.

|

|

Planet 38 by Lisa Shapter

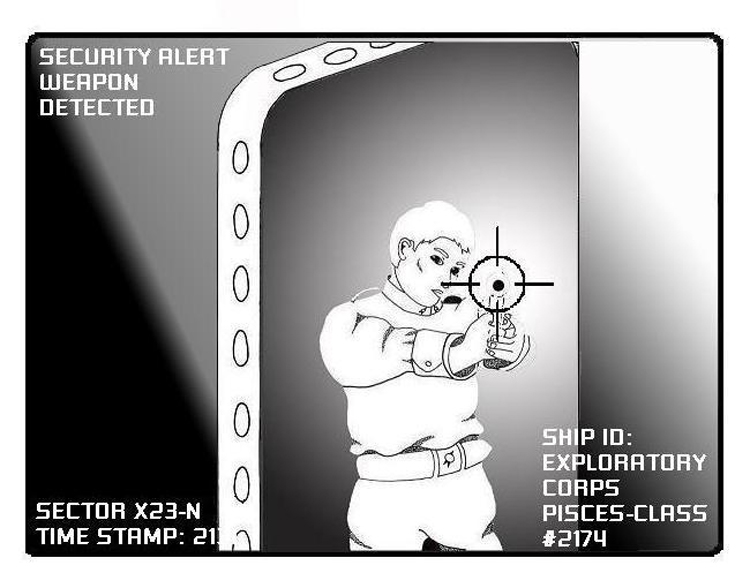

“You can wait on the ship.” I said to the boy, who was only 11. “Nothing is expected of you here or on any world I travel to. You are a Corpsman Prospect, Strath Gestae, not a Corpsman. You don’t have any grown siblings on this world; there’s no one you need to meet.” The young face that was half mine studied me with dark eyes. Unlike the other children stolen from me, this boy had never been taught to lie or hide what he was feeling: he loved me; even though he had only known me a few months. He was afraid for me; he could see that I was frightened and worried. He was learning a hard truth about the Corps very young: Earth’s last military seldom gives distasteful orders (or not ones that are immediately awful). We have no combat, Earth is one world and her galaxy of colonies is carefully designed to prevent armed conflict. Farspace ships have no weapons; they are expected to fly their way out of any difficulties. My orders were terrible: leave my husband and the colony world we were assigned to, travel among 74 colony worlds alone, and meet with the 220-some men who raped me and paid for the children we conceived. They have been punished: I am going to meet all of my children and seek enough reconciliation so we can raise those children together. Eleven is old enough to understand those are terrible orders. But I raised my right hand when I enlisted as a grunt, I vowed to obey any orders given by my CO, I volunteered to let base doctors build a womb on my body (no women from Earth may serve in farspace). My plight would be only slightly worse if I were a natural woman: I have fewer mature pseudoeggs at any one time than a real woman but my changed biology is capable of conceiving more children than any new colony could support. The sarxomorphologists who changed my body could have put limits on my fertility; those base doctors could have had my fertility stop after 7 children, or 10 children, or 12 children--or whatever might seem sensible as the first generation for a newly colonized world. Instead, my system is fertile until the sarxomorphologists turn it off: I am fertile for my entire adulthood in order to account for colonial disasters, miscarriages, and abnormally low fertility rates with my assigned ship’s stock of genetic samples. I have 50 children. Who needs 50 children? Who can raise 50 children? How can I raise them with men who looked at me, shackled to a table, naked, made mute, and thought there was absolutely nothing wrong with that situation? “Mom, are my siblings dead?” Strath asked. “No Honey, they’re in storage. They’re only hours old, unborn, in medical storage cubes. Tiny. I’ll just go out and meet their fathers, and I’ll come back after we’ve talked.” “Will you take a gun?” My son twisted in his child-sized field boots. He looked at the gun locker next to the ship’s atmospheric door. “No, Sweetie, I can’t take a gun. I killed the man who brought me here.” I began to smile at Strath and said, “the Corps doesn’t like me to handle guns. It’s been a long time.” I added. “It might not be awful.” My son was sharp enough not to believe me. The healthy thing, the wise thing, would be to take him back to my world and leave him with people who would help him settle in to a new life. I could not go home, not for any reason. I had gone AWOL once before, the Corps did not trust me to set my own flight plan. “I’m sorry to leave you here alone. You can do anything you like; I don’t expect you to do schoolwork or prepare for your next scout badge today.” I took a breath. “I’ll be back before you know it.” Some mother I am: Strath had been raised by four loving, attentive parents. The only adults this little boy knew were my perpetrators’ team on his world, men who had truly wanted children and were the good parents base shrinks select for. I had the same psychological predictors, but what does good parenting look like in this situation? My son was transparently afraid I would never come back. We were here, the landing ramp was down, and this world’s perpetrators were waiting for me. I had wanted this to be a short ‘be back soon’, but of course it could not be. I hugged Strath and went out to follow orders. There were three men and five children at the base of the landing ramp. There was a light snow on the wind and the last of autumn in every clump of brown grass and caught patch of dry leaves. I had visited climates like this on Earth: I had not grown up in one. I fastened my uniform jacket tighter, felt nervously that the patches for ‘First Lieutenant’ and ‘Gestae’ were straight, then pulled the watchcap out of my jacket pocket. Every eye was fixed on me. Even the children looked hostile. Protocol insisted I introduce myself. “I suppose you all know who I am,” I said, searching each face for some sign of kindness or sympathy. “Get out.” The man with silver captain’s bars said, pushing two medical storage cubes into my hand. “Captain...” The name patch on his battered field jacket was too faded to read confidently. “Captain, I can’t. I am First Lieutenant Resada Gestae, mother of these two children.” I kept one eye on my greeting party as I checked that fact with my medical scanner. There was no trick on this world: these embryos were my two lost children. “By law we share their custody. I am under orders ....” The words died on my lips. All of their faces were hardened, fierce. I would get nothing from these people. “I did nothing to you,” I said softly. The colony’s commander, the world’s mother, gave me a quick, half-shouted recital of what I had done: I had brought down an investigating magistrate, I had set back the colony’s progress, delayed their retirements, upset their children, disrupted their team .... I had not made anyone trade in flesh, I had not asked anyone to lie. I would rather the whole thing had not happened. Alone upon this world and dependent on my two perpetrators for her survival and her children’s survival, this commander had decided to side with them and to imagine that I and my pimp were on the same page. I could not shout back about just what my pimp had done to me, there were children here, their children and my son listening in the ship’s central corridor. I took out my datatablet and pulled up the form that would allow them to refuse custody of our unborn children. I had never yet brought it out on the 37 previous worlds, and it required them to accuse themselves of starvation, disease, abuse, neglect: filing this might loose them their five growing children. I silently handed it to the commander, who tried to break the tablet across her thigh (the one that did not have a womb built onto it.) It was a dramatic gesture, but it did not work: Exploratory Corps field datatablets are made to survive worse than that. She threw it down on the landing ramp; I picked it up. “Mom?” I turned. My young son was coming down the ramp. “I’ll be right there, Honey. Go back in the ship.” The hair on the back of my neck stood on end. The sound of a gun set to ‘lethal’ came from not a meter past my right shoulder. I turned slowly: Strath had a gun raised in perfect form. I had authorized him access to the ship’s targeting range, and he must have persuaded the ship’s computer that I was in mortal danger. It had taken the gun in the doorside locker out of its harmless ‘target practice’ mode and it was now set to kill any animal between the size of a bison and an elephant with one shot. Strath was not close enough for me to grab the gun. I turned back. One of my perpetrators had a gun out and aimed, also set on ‘kill large target’. I could not tell who had drawn first. I was going to be dead the moment either of them fired. It is safe to stand in front of a military pistol set to kill rabbits, but not one set up to shoot anything larger. I dove off the landing ramp as the shooting started and stayed under its shelter until the smell of ozone died away. I did not want to get up, but my grunt’s medic basic got me to my feet and made me survey the scene for the injured or dead. All of the other adults were down, their children had done exactly what they were trained to do: run in perpendicular lines from the direction of fire and take shelter. They were coming around the sides of my ship; I was the one closest to their parents. Each of the three adults had a pulse, and my medical scanner confirmed they had been hit by properly aimed shots at a setting that would only knock them out. Strath, still standing calmly on the ramp with the sidearm lowered, had adjusted the gun to non-lethal at the last possible moment. I was shaking too hard to yell at my son for attempted murder. I did not even know what to say. The other children arrived, my son sat down on the landing ramp and pulled the datatablet out of my hands. “I know you don’t want us here,” he said to the world’s children. “But we’ve got to work something out. We can’t leave until we’ve worked something out.” He pointed to me and then to himself as if these children had not learned Lingua Franca. “If your three parents sign this form, the Corps will take you away from homeworld. I have a better idea.” By the time their parents were awake and I had stopped shaking, Strath had worked out an agreement that his two siblings should remain in storage, at a base hospital, claimable only by mutual consent of all of their parents, until all of us should die (or reach a mutually agreed upon arrangement for bearing and raising the two embryos.) Strath shook hands with his five counterparts, saluted the world’s commander, and took my hand to lead me back into the ship. I waited until the landing ramp was up and the door shut. “Young man ...” “He raised his gun first. It was set on lethal.” Strath said, knowing farspace law permitted him to respond in kind. “You ...” “All the grownups signed it.” He put the gun’s safety back on, presented it to me, his commander and mother, for inspection then stood on his toes and stored it back in the locker, where it became useful only for target practice. “We ...” I began at last. “Let’s get back to base; we’ll head to the next world as soon as we can.” Strath said as he thumbed the doorside panel for a hull integrity check and turned aft to do the preflight checklist. I watched the skinny figure in a baggy field uniform walk down the ship’s corridor. He can’t go up for command training until he’s 17. Until then I have to raise him. END

|

|

[Index] [About Us] [Stories] [Story 1] [Story 2] [Story 3] [Story 4] [Guest Art] [Editors Write] [Archives] [Contact Us] [Links] Copyright © 2013 by 4 Star Stories. All Rights Reserved. |